A long time ago, the original marketing materials for Windows Autopilot (before it had a name) were created by the engineers working on the product. It pitched Autopilot as a way to simplifying the out-of-box experience (OOBE) for Windows, even though it was Microsoft that made OOBE so complicated in the first place. Obviously that positioning was modified to something that wasn’t quite so cynical.

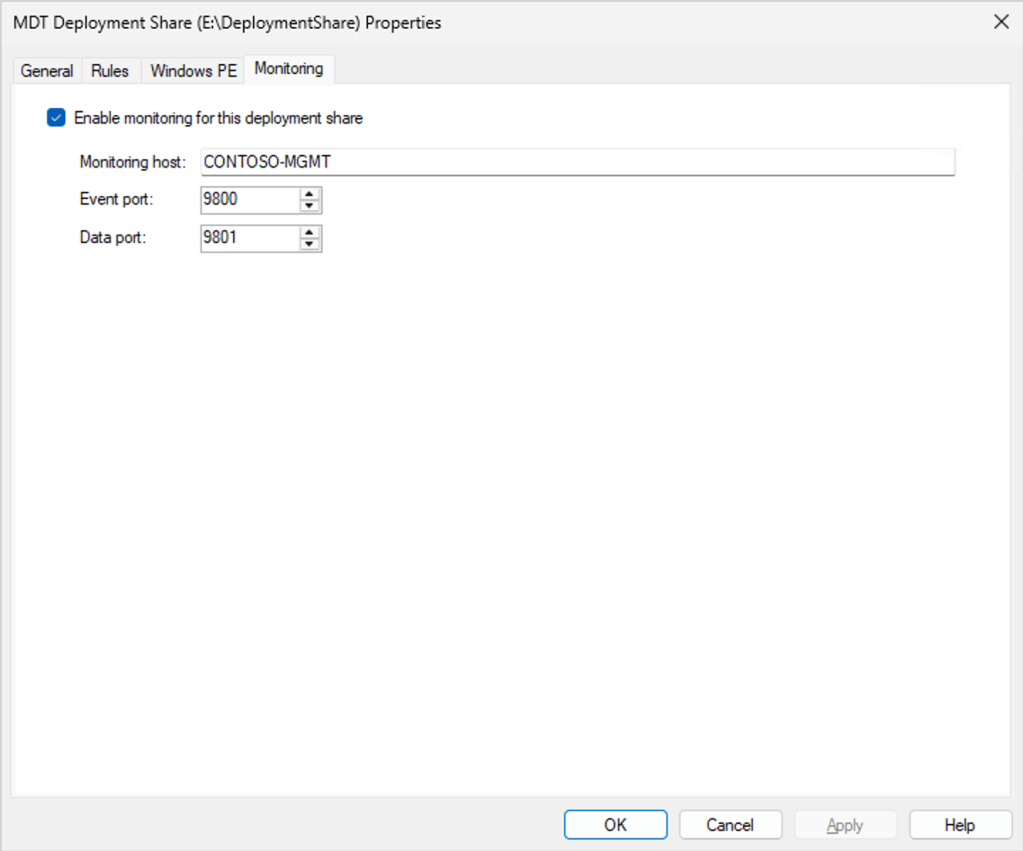

But how complicated is OOBE anyway? To get a rough idea, the diagram below shows all the “nodes” in the OOBE navigation process. This was created from the “navigation.json” file from Windows 11 24H2, which you can find at “C:\Windows\SystemApps\Microsoft.Windows.CloudExperienceHost_cw5n1h2txyewy\data\prod\navigation.json.” The “main” flow through OOBE is “FRXINCLUSIVE.” Each defined node specifies what the “next” node should be in the case of success; the diagram below shows that “success” flow, starting from the “StartSelector” node at the bottom center and working all the way through.

Simple, right? (You can see a few floating nodes, as well as a few small subgraphs. Those can be related to failure paths, or sometimes just explicit, programmatic “go-to” paths.)

If you want to see the full image you can access that here:

https://mtniehaus.github.io/Misc/OOBE.html

Start from the “StartSelector” node toward the bottom center and work your way around from there.

Not all of these nodes actually product a UI; some just perform processing. Looking through the list, here are some notes on some of these:

- AutoPilotPrefetch. If the device has Ethernet connectivity, it can download the Autopilot profile very early in the process and use that to control the flow after that point, e.g. skipping the language, locale, keyboard. If it can’t do it then, it will do it later in the AutopilotActivation step.

- OobeZdp. This is the first place that OOBE can install updates. This isn’t the typical cumulative updates though. Instead, it’s intended just for critical “zero day patch” (ZDP) updates that fix issues with OOBE itself (and perhaps some critical driver updates that would otherwise stop OOBE from completing successfully).

- AutopilotUpdate. There is still a point where an Autopilot-specific update could be installed, swapping out the Autopilot binaries. That’s not been used for a few years, and never was quite successful, so it will probably never be used again.

- AutopilotDeviceRename. This is used with Azure AD/Entra ID join to set the computer name to the pattern specified in the Autopilot profile (impossible to do right now in Autopilot v2/Autopilot device preparation, since this is too early in the process).

- AutopilotVetoESTS/AutopilotVeto. It used to be possible during a self-deploying scenario to abort out of the process — you just needed to click a button before it timed out. This was useful for testing, but was turned off later — but the logic is still there. If you “vetoed” the Autopilot deployment, it would start over as a non-Autopilot device.

- OobeDeviceName/OobeDeviceNameReboot. On Windows Pro, Windows will prompt for a computer name, and then reboot after the user types it in. This is suppressed for Autopilot v1, but not for Autopilot v2 (since the device doesn’t even know that it will be doing Autopilot v2.). You won’t see this on Windows Enterprise.

- OobeDomainJoin. It appears that OOBE is still able to do Active Directory join, but I don’t think this has ever been enabled…

- OobeSettingsSelector. I believe this decides which branch is needed, then all of those branches navigate back to that node. So you could have Azure AD/Entra ID join, MSA, HAADJ domain join, self-deploying, white glove, etc.

- “PlugAndForget”. Any node that mentions “PlugAndForget” is talking about self-deploying Autopilot; “plug and forget” was the original internal name. Notice that pre-provisioing (originally called “white glove” but that was considered an insensitive name) shares some of the same logic, since it uses that behind the scenes: TPM attestation, joining AAD with a device token, etc.

- DevicePreparationPageAfterAAD. If you follow the branch from “OobeAAD” you’ll see where Autopilot v2 comes into play. Until the AAD join and MDM enrollment is completed, the device doesn’t know if it needs to do anything related to Autopilot v2, so this is the point where it realizes that is the case.

- Look at the sub-graph that starts with “OobeOemRegistration.” This is where all the “junk” starts. In addition to the OEM-specific registration pages (the OEM includes an HTML page to do that), there are pages to pair with your phone, to set up OneDrive, to sync settings to Edge (from Chrome?), to get Office 365, to sign up for Game Pass, etc.

- See those NDUP pages? Rudy talked about those in his blog post. These install the latest cumulative update at the end of OOBE (now postponed). It’s interesting that these occur in the MSA process too, but earlier in the process — maybe these can eventually happen earlier in the Autopilot flow too (or just all the time).

- I believe the “OobeSettings”-related nodes are what prompt for security and privacy settings; these are suppressed during Autopilot v1, but not for Autopilot v2 (for some reason).

Have fun browsing through the diagram to see if anything catches your eye.

3 responses to “How complicated is OOBE?”

Wow, you’re the man – thanks for your service 😀

LikeLike

Thank you for all of your post! They are really helpful. I noticed in one of your post that your device was listed as a virtual machine, is there a post that explains how to setup deployments and test on virtual machines?

LikeLike

It depends on what you are looking to do. A post on the topic: https://oofhours.com/2023/08/23/windows-autopilot-testing-with-vms/

LikeLike